Imprints

By Antonio Ramblés

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

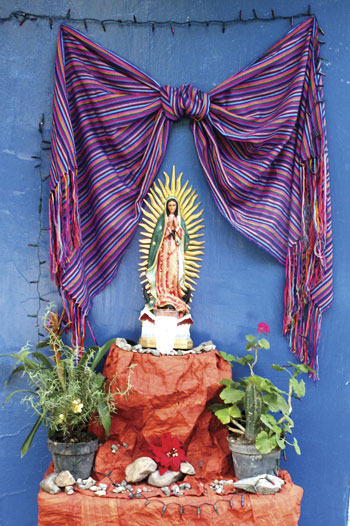

Altared States

In Mexico, altars are not found just in churches. Makeshift and highly original altars appear on highways throughout Mexico as poignant reminders of traffic fatalities, and they’re a signature facet of the Dia de Los Muertos.

In Mexico, altars are not found just in churches. Makeshift and highly original altars appear on highways throughout Mexico as poignant reminders of traffic fatalities, and they’re a signature facet of the Dia de Los Muertos.

On each December 12, they honor the Virgin of Guadalupe, Catholic Mexico’s patron.

In many towns, several days of public observances lead up to the holiday, but on the afternoon of this December 12 in the village of Ajijic, families are still putting the finished touches on freshly constructed altars.

I walk the cobblestones streets capturing their images as I reflect on the tradition.

Catholicism has a long history of incorporating and reshaping local religious deities into its observances to ease the path to conversion, but perhaps nowhere has the practice taken a more remarkable turn than in Mexico.

The legend has it that ten years after the Spanish Conquest, a Mexican native named Juan Diego saw a vision of a brown-skinned maiden on a hill near Mexico City which had once been the site of a temple to a female Aztec deity.

Speaking to him in his native tongue, she asked that a church be built at that site in her honor. He was instructed by the city’s archbishop to return to the hill and ask for a sign to prove the lady’s identity, and then she healed Juan’s sick uncle. She also told him to gather flowers from the normally barren hill, where Spanish Castilian roses now miraculously bloomed.

She arranged the flowers in his cloak, and when he opened it before the archbishop on December 12, they fell to the floor to reveal the image of the Virgin on the fabric.

To the indigenous peoples, the vision was interpreted as a legitimization of their own Mexican origin.

As the common denominator among the varied tribes which make up Mexico, it’s no surprise that the Virgin is sometimes referred to as “the first mestiza”, or “the first Mexican”.

Part of the power of this image for indigenous Mexicans was the pre-Colombian symbolism with which it is imbued.

The blue-green color of her mantle was once reserved for the divine couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl.

Her belt symbolizes pregnancy, and a cross-shaped image symbolizing the cosmos and called nahui-ollin is inscribed beneath the image’s sash.

She was also called “mother of maguey,” the source of the sacred beverage pulque, which was also known as “the milk of the Virgin.” The rays of light surrounding her are interpreted to represent maguey spines.

Although the Virgin is the recognized religious symbol of Catholic Mexicans, she is also closely intertwined with the spirit of Mexican nationalism.

Mexico’s first president changed his name to Guadalupe Victoria in her honor, and patriot armies carried flags emblazoned with her image during Mexico’s War of Independence and the Mexican Revolution.

When the army led by Padre Miguel Hidalgo, the father of Mexican independence, attacked Spanish Royalists, they placed her image on brightly colored reeds and wore the same image on their hats.

Hidalgo’s grito, the hallmark cry of the battle for Mexican independence, ends with the words…”long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!”

Following Hidalgo’s capture and execution, his successor José Morelos declared that the Virgin was the power behind his victories, and her image was incorporated into the seal of the Congress of Chilpancingo.

Her feast day was also written into the constitution. In this century, Mexico’s revolutionary Zapatista National Liberation Army named their “floating capital city” Guadalupe Tepeyac in honor of the Virgin.

Latin American liberator Simón Bolívar wrote, “… the veneration for this image in Mexico far exceeds the greatest reverence that the shrewdest prophet might inspire.”

Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes once said that “you cannot truly be considered a Mexican unless you believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

Nobel Literature laureate Octavio Paz wrote that “the Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery”.